Going to work during a pandemic has been a strange experience for pretty much all of us, but for Harvard epidemiologist Christopher Golden it’s been particularly surreal: He has spent most of the pandemic traveling around the world studying the conditions that can produce pandemics. For added strangeness, a film crew has been following him as he goes.

The result of this surreal adventure is an urgent, taut new documentary, Virus Hunters, that premiers today on the National Geographic Channel. On one level, the movie follows a fairly standard detective story format, but it subtly develops a deeper theme. It’s easy to develop a false idea of viruses as entities that we encounter only sporadically. The COVID-19 pandemic has, if anything, reinforced that impression: Wear your mask, maintain safe distance, wash your hands, and you can hope you’ll never encounter the novel coronavirus.

Virus Hunters conveys a different impression. We live on Planet Virus—or, perhaps more accurately, we are swimming around on Planet Virus. There are far, far more viruses on Earth than there are stars in the observable universe. If you lined up all the viruses end to end, they would stretch … what, to the moon? To the sun? No, they would stretch 100 million light years! There are a lot of viruses on this planet.

The vast majority of the time, we live in harmony with the viruses around us. What Golden and other disease detectives are trying to do is identify where and how humans get exposed to new, dangerous viruses like SARS CoV-2 (the cause of COVID-19). That task requires understanding human nature every bit as it requires understanding virus nature. And so Virus Hunters is a story of people and culture and bad decisions every bit as much as it is one about proteins and RNA.

One of the early lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic is that people are very good at forgetting the lessons of previous pandemics. Golden wants things to be different this time around, and Virus Hunters is part of how he’s trying to make a lasting change. I spoke with him about his work and about the unique circumstances under which it was made. A lightly edited version of our conversation follows.

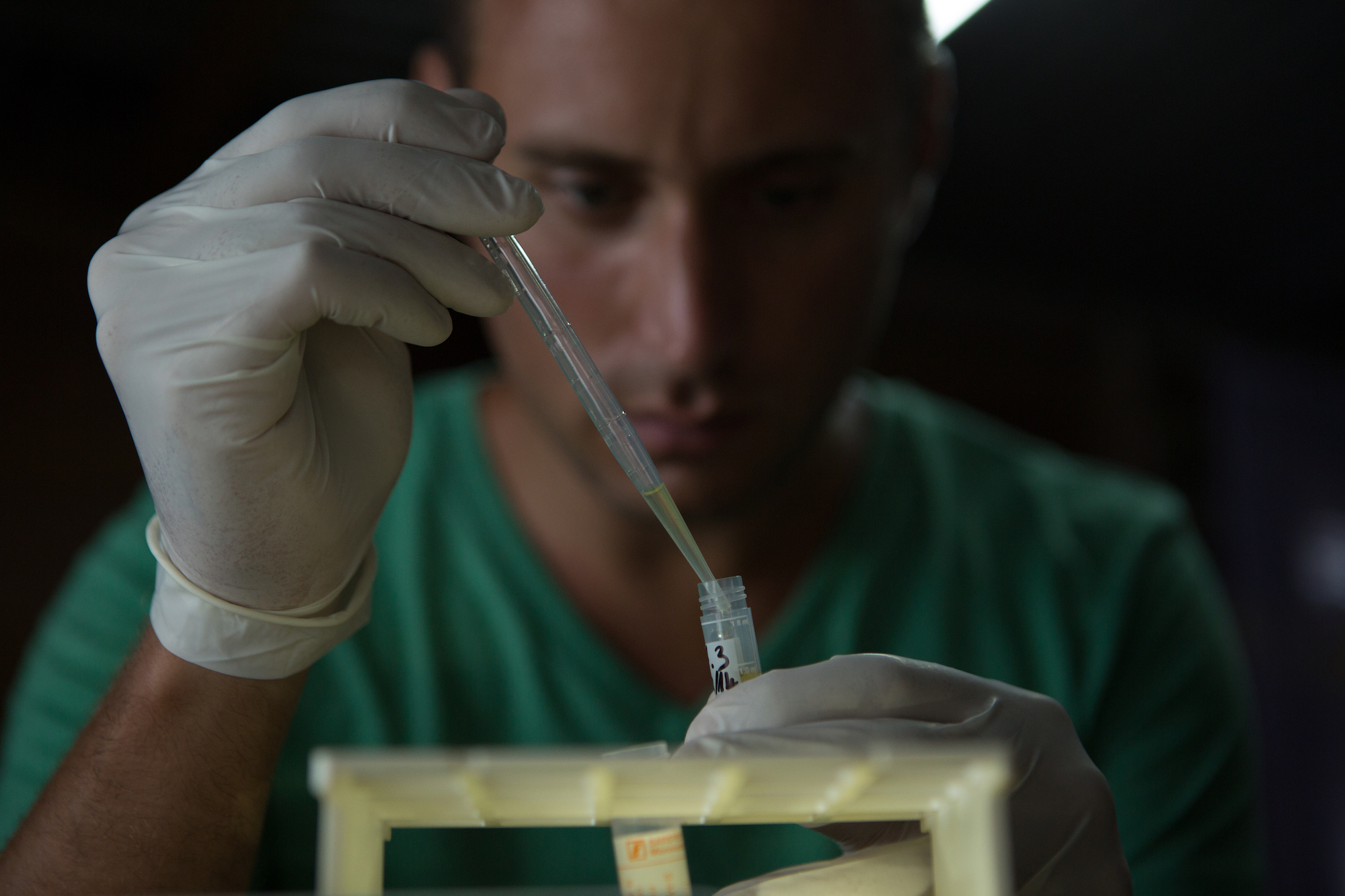

Chris Golden, doing what he does best: collecting virus samples while trying to stay extremely safe. (Credit: NatGeo/Jon Betz)

Q. How did you become a virus hunter?

A. I wouldn’t exactly call myself a virus hunter. A lot of Virus Hunters is about the broader field, documenting and characterizing the potentially novel viruses, pathogens, and bacteria that exist within wildlife, and which could lead to spillover events. I’m more of a planetary health scientist, ecologist and epidemiologist who’s really focused on looking at the root causes that could lead to disease margins. I’m trying to understand the environmental trends unfolding around the world that are leading to impacts on our own health.

Q. Media coverage of SARS-CoV-2 often highlights the danger of “wet” markets that sell live or butchered wild animals. Those markets show up in the film as well. Is this the right problem to focus on, and if we could crack down on wet markets would it make a significant impact in the spread of disease?

A. I don’t think so. This is an important piece of the puzzle, but it is definitely not comprehensive of all of the risk factors that exist. There’s a lot of nuance here, and a lot of misunderstanding. When people eat wildlife, and when they’re receiving a dead animal and cooking it, the risk of viral exposure is incredibly low. The risk from bushmeat [wild animals

caught and sold], and how it can drive disease emergence, is that it creates an economic market that drives hunters into the forest. They become more and more exposed to live wildlife that’s then hunted, butchered, and transported.

Where you have fresh blood and interaction with human skin—or with cuts or blood itself—that’s really where you’re going to have these types of exposure events. The market itself is not the problem, the economic demand created by the market that causes hunters to flood the forest is really the problem.

Q. I’m sure you’ve heard people say, “COVID happened because some guy ate a bat.” Is that kind of shorthand helpful in highlighting the problem, or harmful in oversimplifying it?

A. I would say it’s both. It is helpful in having people understand that the interconnection

between people, planet, and wildlife is an important dynamic to understand to best protect our own health. But it’s also harmful and very nearsighted, in that proximate interaction is what’s really driving all of this.

What we really need to do is to understand all of these root causes that are bringing people into more contact, and closer contact, with wildlife and domesticated animals. Deforestation, mining, agricultural expansion and all of these other activities that are reshaping the surface of the Earth are what is causing people to come into closer contact and enabling these exposure events to occur.

Q. The world has gone through many cycles in which people ricochet between panic and complacency toward emerging diseases. How can we break out of that pattern and build a more sustainable strategy?

A. This is such a tricky question, and it goes beyond my expertise. It really requires people that understand dimensions of human psychology, motivations, and things like that. My main recommendations would be: We need to take time to grieve everything that’s happening right now [with COVID-19], but we also need to use this experience as motivation for how we prevent the next pandemic, or how we deal with the next pandemic.

And we need to do a few things differently. We need to be very conscious of what we’re buying, of what we’re eating. We need to ensure that we have institutions in place that respect science, and can allow public health practice to be streamlined in an efficient way across our country. One of the many steps to take in the U.S. is to vote on Tuesday, and to cast an individual decision that you want to create a healthier society.

Q. I know you’re still adapting to being in the public eye—and you’re about to become very public in Virus Hunters. What was it like going to those extreme locations, having those intense experiences, all while there’s a film crew hanging around?

A. It’s really interesting. As an academic, I’m used to giving public talks. I thought that there would be a similar vibe to this, but it’s completely different. The crew is around you so much that they just become friends and you forget that the cameras are there. Also, we had such an incredible team, working hard to ensure that we were safe, happy, and having

fun all along the way. We created our own bubble during the pandemic and traveled around together.

Bats and birds are common reservoirs for viruses that can “spill over” to people—often during encounters in the wild. (Credit: NatGeo/Carsten Peter)

Q. You traveled all around the world in that bubble. Did anything you encountered change your view of infectious disease?

A. It was amazing to see not only all of the research that people were doing, but to visit countries that had very divergent policy responses to the pandemic. We went to Liberia, which had been ravaged by Ebola with devastating consequences. So when the news of this novel coronavirus began to emerge in late January, people in Liberia took it very seriously. There was immediate action. There were people wearing masks, the borders were being controlled, there were hand-washing stations in front of every building. To

date, they’ve had less than 200 deaths.

This is something really important to understand: Being proactive, being precautionary, and really taking these things seriously is so important to minimizing the potential impact that a new pathogen could have on a population.

Q. How much of Virus Hunters was made during COVID-19?

A. The entire filming process was during the pandemic! We were one of the only film crews going out around this time. We did everything in as safe a manner as possible, to really protect ourselves. Yes, travel is an important risk factor, but when we were in these other countries, we just felt much safer, because there’s such a lesser burden of disease in all of these countries with regard to COVID.

Q. That’s counterintuitive, that you felt safer about the pandemic while you were traveling in the developing world. Did you have to communicate that message to the crew?

A. Everyone was coming from very different places. There were parts in our crew coming from Florida, from Portland, Oregon, New York City, so people had very different experiences with the pandemic. For many people, this was the first time that they were leaving their homes and doing anything since the pandemic began. I was initially scared just going to the grocery store and picking up stuff, and then we were suddenly leaving the country. It was new for all of us, trying to wrap our heads around what was a risk factor, what was not, and how to practice the best kind of safety.

Q. Completely apart from COVID-19, many of the locations you visit in Virus Hunters look potentially risky. Were there any times during filming when it felt frightening?

A. Frightening isn’t the word that I would use, but there were definitely things that surprised me, and shocked me along the path of filming and production. Two examples come immediately to mind.

One was the scene where we descend into a bat cave to look at the enormous amount of human interaction that’s happening there. There are people who collect bat guano there; they had left all of their belongings and bags of guano in the cave. We were going down there and seeing that this is the exact type of scene where viral spillover of people getting infected could occur. There were aerosolized feces and urine, and bats swarming overhead. We were wearing protective equipment, but the people who were collecting guano are not practicing that type of safety.

Q. What’s the other situation that you found unsettling?

A. It was in the bushmeat market in Monrovia, Liberia. I’d never seen a wet market at that scale. Madagascar, where I’ve worked for a very long time, doesn’t really have a commercial market for bushmeat. It’s more about localized hunting for people who are poor and need food. But in Monrovia, there is an urban demand that’s sucking wildlife out of the forest in rural areas, and bringing it into urban markets. To see the scale of bushmeat consumption that was happening in the cities — deer, primate species, porcupines, carnivores, all of these different things lying on the table, and ready for sale — it was definitely a shock.

Q. People watching Virus Hunters will obviously be viewing it through the lens of COVID-19. Do you see any helpful lessons that we’ve learned from the pandemic so far?

A. It’s hard to talk about silver linings when there is so much devastation happening. There are so many lessons that have fallen on the backs of the people who have died during the pandemic.

I think the main upside is that people are increasingly aware of this inextricable connection between people and planet: The way that we take care of the Earth is going to have feedbacks to our own health and well-being. I think that we, as a society, have greater faith in scientists now, and will be able to have a credible trust with institutions that they will be able to take care of us.

The failure of leadership exhibited during this administration’s practices, of trying to reduce the impacts of the pandemic, is something that really highlighted how important leadership is. We urgently need to be thinking not only about domestic policy. All of the decisions that we make in a society, particularly here in the U.S., have global impacts. The decisions you make about what you buy, and what you eat, and what you choose to do, will have rippling effects on all corners of the Earth.

Q. What about your own research? What are you working on now, and how are you hoping to contribute to these solutions?

A. There are two main projects I’m working on right now. One is developing a climate-smart public health system in Madagascar. We trying to develop and harness a system of health monitoring and surveillance that is coupled with all of the potential climatological, environmental, and agricultural variables that you can think of. In doing so, you can understand how changes in one of these systems has downstream effects on another system. Then you can practice careful, science-based policy to say, “OK, if we’re going to

do an agricultural intervention, what type of impact will that have on health? What type of impact will that have on the environment?” And you can begin to have more holistic action across sectors.

The other project that I’m working on is to understand how what we’re doing to the oceans is going to affect food security. I’m trying to understand how sea temperature rise, coral bleaching, and over-fishing, for example, are driving reductions in fish catches around the world. The changes are significantly reducing a critical form of nutrition for many people, particularly in the global South. At the same time, interventions like marine protected areas, fisheries reforms, aquaculture and mariculture innovation and collaboration could produce significant amounts of food that are less burdensome on the planet.

Q. Which brings you back to the connection between food scarcity, bushmeat, and infectious disease.

A. Exactly. It’s all connected.

For more science news and commentary, follow me on Twitter: @coreyspowell